| « What is faith? | City council » |

6 Passages That Weren't in the Original New Testament

The printing press was invented in 1439, so for the first 1400 years of Christianity all of the books were copied by hand. For the first 300 years, that work was done by literate church leaders rather than by a class of professional scribes and monks as was the case later on. The same Christians that were preserving and copying the texts that became the New Testament were also embroiled in several theological debates. We now know, based on comparisons of the surviving manuscripts from the history of the Church, that those early copyists made changes to the text. Most of those changes were minor mistakes like spelling, word order, skipping a line or just a simple misreading. But in some cases, entire verses or passages were inserted by the scribes to bring the text in line with their theological views and to bolster their position in the debates of the day.

1. Mark 16:9-20

What it says

Our most reliable early manuscripts of the Gospel of Mark end with Mark 16:8, which says that some women discovered the empty tomb of Jesus, but never mentioned it to anyone. This may have been all there was to the story when the Gospel of Mark was written, but when church leaders were copying this book more than a century after it was written, this abrupt ending must not have seemed right to them. So, they added some post-resurrection appearance stories and a commission from Jesus calling people to be baptized, speak in tongues, heal people and handle deadly snakes without being harmed.

Why they changed it

By the time this passage was added, the other Gospels with their post-resurrection appearances and ascension accounts were well-known throughout the early church. The abrupt and unimpressive ending of Mark may have been a source of embarrassment for the church. It served as a record of the changes that had already been made to the stories about Jesus. The addition of this ending brought Mark in line with the other Gospels and smoothed over this inconsistency. (I also discussed the ending of Mark here.)

2. John 7:53-8:11

What it says

This passage contains the story of the woman caught in adultery. It is the source of the iconic phrase "Let he who is without sin cast the first stone." Although it is a charming story about grace and forgiveness, the textual evidence suggests that this passage was not in the original version of the Gospel of John.

Why they added it

There's no obvious reason for the insertion of this story. It may have simply been a part of the oral tradition about Jesus that was added to the margin of a manuscript by a scribe and inserted into the text by a later scribe. Interestingly, we have manuscripts that insert this story at different points in the Gospel of John. One scribe even stuck this story into the book of Luke. Most modern translations include this passage but label it as a later addition. If you see the Bible as a book written by a perfect God and transmitted by fallible humans, then you must discard this passage as a human invention, which is a shame because it teaches a nice lesson.

3. John 21

What it says

John 20 ends with what looks like a closing statement:

Jesus did many other miraculous signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.

John 21 seems like it was tacked on to an already finished book, but there are no surviving manuscripts that omit John 21. So, the only evidence that this passage was added by a scribe is the internal evidence of the text itself. If it is an addition, that would help make sense of John 21:24 which speaks of the author of the book in the third person.

John 21 seems like it was tacked on to an already finished book, but there are no surviving manuscripts that omit John 21. So, the only evidence that this passage was added by a scribe is the internal evidence of the text itself. If it is an addition, that would help make sense of John 21:24 which speaks of the author of the book in the third person.

Why they added it

This chapter includes the reinstatement of Peter, who had denied Jesus a few chapters earlier. This addition resolves that story line. Perhaps some early scribe listed an example of those "many other miraculous signs" after the end of the book (borrowing a story from Luke 5:1-11) and the next scribe copied that section as if it were part of the text. But if that happened, it was already done before our oldest manuscripts of the Gospel of John.

4. Luke 22:17-21

What it says

Here is the passage as it appears in the NIV, with the added passage in bold:

After taking the cup, he gave thanks and said, "Take this and divide it among you. For I tell you I will not drink again of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes." And he took bread, gave thanks and broke it, and gave it to them, saying, "This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me." In the same way, after the supper he took the cup, saying, "This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you. But the hand of him who is going to betray me is with mine on the table.

Why they added it

One of the theological debates that raged in the early church was about the meaning of the death of Jesus. Each Gospel has its own perspective on the significance of that central event, and each of those views had its defenders in the early church. Outside of this passage, the Gospel of Luke describes the death of Jesus as a miscarriage of justice and an occasion for repentance, but not as a sacrifice for sins. The addition of these lines to the text serves to bring Luke into agreement with what became the Orthodox view of the death of Jesus. The language that was employed here is very similar to what's found in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26.

5. Luke 22:43-44

What it says

An angel from heaven appeared to him and strengthened him. And being in anguish, he prayed more earnestly, and his sweat was like drops of blood falling to the ground.

Why they added it

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus is always calm and collected, never letting his emotions get the best of him. Although several of his stories were copied (almost) word for word from Mark, the author of Luke always left out the parts that showed Jesus getting angry or upset. These two verses interrupt the flow of the passage, they don't fit in with Luke's usual portrayal of Jesus and they are not present in our earliest copies of the text. But why would this be added?

One of the theological controversies in the first few centuries of the church surrounded the question of who Jesus was. Was he a man? Was he God? Was he both? All three of these views were present in the early church. The latter ultimately won out and the other views were declared to be heresy. Luke was the gospel of choice for those who said that Jesus was a divine being who only appeared to be human. Some scribe inserted this passage so that Luke, like the other Gospels, attributed human emotions to Jesus.

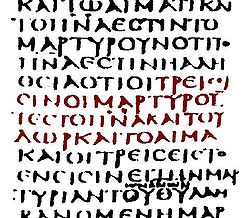

6. 1 John 5:7-8

What it says

For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.

And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one. (KJV)

Why they changed it

The first line of this passage is not present in any manuscripts produced before the 16th century. All Bible scholars now recognize that this passage was inserted to improve the case for the doctrine of the Trinity, which is not clearly stated in the Bible outside of this added passage. Most translations of the Bible now omit the added passage or relegate it to a footnote. The King James version includes this passage because it was translated from late and unreliable Greek manuscripts.

Why it matters

Textual criticism is the field of study that attempts to discover what the original version of the Bible said. This is especially important for Christians who believe that the New Testament was inspired by God. If some passages were added or altered by human scribes, then those must be discovered and stripped away so we can get closer to the original text. But those changes also tell us something about the early church leaders. Many of them did not see the New Testament as an immutable document delivered from God, but as a text that could be changed to bring it in line with official church doctrine.

Perhaps you see these as a minor changes that don't affect the central message of the New Testament. I wouldn't consider the identity of Jesus, the doctrine of the Trinity and the meaning of the death of Jesus to be minor issues. But there is another, bigger problem with brushing these changes aside. They are probably only the tip of the iceberg. The oldest surviving copies of several books in the New Testament were made over 100 years after the original text was written. There may have been very significant changes to the text during that interval, but in the absence of manuscripts we don't know what they were (unless we rely on internal evidence as in the discussion of John 21 above). There's no reason to think that the copyists of the first 100 years were any more shy about making changes than the copyists of the next 300 years.

The changes that we know about show that even if the original books of the New Testament were inspired by a god, they were not miraculously preserved. That job fell to humans who introduced thousands of unintentional and intentional changes. So, even if you can come to terms with the changes I've listed above, you must also face the possibility that there are many more changes that we will never discover. And if the scribes were willing to make changes, then the Gospel authors probably were, too. In fact, we can see that Matthew and Luke took passages from Mark and made changes to them.

There are a lot of good ideas and stories in the New Testament, but I don't see how anyone can view it as a perfect book without disregarding loads of evidence.

(Much of the information for this post came from Misquoting Jesus by Bart Ehrman. It's a good introduction to textual criticism.)

8 comments

1. “It served as a record of the changes that had already been made to the stories about Jesus.” You will not find many scholars who agree with you that the resurrection was invented between Mark’s Gospel and the rest. Even the Jesus Seminar dates Paul’s creedal formula in 1 Cor 15 to within 3 years of Jesus’ death. The most fantastic elements of the resurrection account were already believed for 30+ years before Mark ever sat down to write his Gospel and not include them. The question then becomes, why did he not include something that he knew was widely believed and that he himself believed?

2. A nice story, yes. John does read much better without it, but it is hard to get rid of. Would be nice to know if it actually happened–that would be cause for keeping it. I rank it somewhere below the rest of the Gospels material, but still quite above, say, that “Footprints” poem.

3. Your hunch is that this is an addition, but there is no textual evidence. This sounds like a “Scribe of the Gaps” theory to me. Your preference for the version of the story that you deem most damaging to faith is directing your conclusions. Now at least you can admit that you’re doing what everyone else does with the texts, just in the opposite direction? At any rate, the third person allusion to the author is actually in keeping with the verse just above (21.20-23), which is similar to other passages in John’s Passion account (20.3ff, 19.26-27, 18.15ff, 13.22ff).

4. To make your point that this was added to bolster one side in a theological controversy, you would need to trace the manuscripts down, date them, and see if there is any evidence whatsoever to make this claim. Perhaps there is. But a general lay reading of church history is not nearly enough evidence for your conclusions. That Luke doesn’t make Jesus’ death out to be a sacrifice for sins is easy enough to understand, since he was writing to Gentiles and the language of sacrifice would not have been as powerful to them. But there are many other atonement theories than just the image of sacrifice, and it is incorrect to suggest that only the sacrificial understanding sees Jesus’ death as salvific. Finally, it does not seem all that uncommon for a scribe to go on “autopilot” and accidentally introduce familiar language into a passage where it does not originate. The passage from 1 Corinthians 11 seems to have been then what it is now: a formula that was often recited during communion.

5. Again, to actually make (rather and suggest) this claim, you would need to trace the manuscripts to the dates and places of these controversies. I think Luke is clear enough that Jesus was human–he is one of only two that speaks about his birth and early life, he mentions that he was hungry after fasting, he feels strongly for a widow whose sons had died, etc.

6. “All Bible scholars now recognize that this passage was inserted to improve the case for the doctrine of the Trinity, an idea which is otherwise foreign to the New Testament.” A nice way of linking scholarly consensus on a point of textual criticism to a conclusion that you, and not “all Bible scholars,” believe–that Trinitarian doctrine was invented after the NT was finished. There need to be some clearer divisions between the data and your interpretation, but we all have that problem.

You ask the question later, What else will we find out about what was changed in those first 100 years? That obscures the fact that getting manuscripts within 100 years of their originals is better than pretty much every other ancient document. If we can be sure that any document from antiquity has been faithfully preserved, the New Testament stands first in line–indeed, you can only criticize the changes by the overwhelming presence of reliable manuscripts. To call into question their reliability would call into question even more the other ancient documents we have. In terms of historical certainty, we would have to give up quite a bit of what we consider history.

It seems like you are trying to refute the dictation theory of inspiration. So what? That may be the way that you thought of inspiration while you were a Christian, but that doesn’t mean that it’s the only way to believe, and it certainly doesn’t mean that it is a widely held belief throughout the centuries and across the world. The dictation theory has a standard of faithfulness that is different from other ideas of how the NT has come to us. You can’t attack the most rigid standard that is not all that widely held among theologians and reasonably expect to convince people that the Christian faith is purely human invention.

1. That Mark knew nothing of Paul–They are thought to be companions, and Mark is the reason why Paul and Barnabas split. At any rate, the movement was probably a bit too small at that point for someone like Paul to be missed. And Paul claims both the vision and the party line. The vision supports his claim to be an Apostle, but so does consistency with the apostolic witness. As for the ending of Mark, I think of it like an unresolved ending. The disciples are, it would seem, about to set out to find the risen Jesus in the world around them. By the time we get to the end with Mark inviting us to take the disciples’ perspective in the drama, I think it may have been his intention to urge us to go meet Jesus in the world around us. Considering the time of persecution and scattering that the church was beginning to endure at the time, this would have been a great encouragement (at least as I imagine myself in that situation). As to the Jesus Seminar, it is anything but conservative. A few atheists have been pretty heavily involved, as well as not too few liberal theologians. Your comments generally line up quite well with their conclusions.

2. I always try to reference Footprints. I used to annoy people by saying it was my favorite Psalm. It’s funny when people buy a Bible cover with that poem embroidered on it. At least they’re being honest that that’s the lens through which they are reading.

3. No props for “Scribe of the Gaps"? 21 is not quite a post-resurrection appearance like the others that close out 20, and it fits a different purpose (as you point out in the original post). There is a bit of a stop and start there, but I think of it more like a fade to black followed by an epilogue.

4. Could be a decent explanation if it pans out, but the point is that there isn’t evidence presented here for that yet. To be true to your epistemological values, I think judgment ought to have been reserved. Otherwise, you appear to make judgments in favor of your preexisting beliefs before sufficient evidence is considered.

5. True. I should look into that.

6. I would say that most doctrine finds its foundation, but not its full expression, in the New Testament. So the decision of various Councils and the writings of so many theologians work out the logic of the NT in faithful ways. Obviously, some doctrines are more central than others, and therefore deserve greater attention. Also, saying “the early church didn’t agree” when you’re referring to the Gnostics and other sects assigns these groups a place within the church that even some of the NT writers did not want them to have.

7. About the time between original autographs and extant manuscripts: It becomes difficult to know what we can say with certainty about the past. At some point in questioning the historical foundations of the New Testament you reach a point where you can no longer say anything meaningful about any history from that time period. The point is that disbelieving the NT because of its theological implications is not necessarily good historical work, nor is it consistent. I think NT Wright made the point once that the one unquestionable historical fact (the invasion of Rome, I believe) comes from a passage laden with tales of dreams and visions. Unless an atheist wrote, you’re not going to find the kind of theologically neutral history that you seem to seek–whether you’re considering the NT or other historical documents. Finally, why would anyone become a scribe unless they were motivated by their religious convictions? You seem to suggest that the only scribe you would trust is one who would dedicate some portion of his life to copying documents he did not believe to be true but thought it would be historically interesting to preserve for later antiquity. That’s pretty anachronistic and highly unlikely.

8. About fundamentalism: I think I see your point. I normally read your posts as if you and I are sitting across the table from one another (with one game or another in between us), so I typically imagine that you are trying to convince me. And maybe you are; after all, I may not be causing as much harm, but perhaps a little?

I am about to go off and present at the national conference for (secular) textual scholarship, so it was kind of funny to run into your post today. I really should be editing my paper, actually, but this discussion is too strong a temptation.

I guess I’m sort of like Peter. I know most of the facts you cite above, and I wouldn’t contest them. They don’t really bother me or most of the Christians I hang out with (we actually discuss these textual questions in small group Bible study from time to time), so I guess I’m not really your audience…but then who are you talking to really? Maybe there are some hard-core dictational-view fundamentalists who read this blog or who will stumble on it, but I think they’re more likely to find ye olde Blog Cabin when they search for “Top worship songs,” and then they’ll be content to hang out back in 2004, unaware that there are any other posts on this blog, calling Sara and the rest of us deceived heathens.

I think you’d still strongly disagree, though, with my (and I assume Peter’s) view on the big issues you cite: “the identity of Jesus, the doctrine of the Trinity and the meaning of the death of Jesus.” These are understandings, I think, which one would get if you read the whole of the texts which would have been approved by the original authors (ok, maybe not a fully developed notion of the Trinity, but something sort of like it). No, not every Gospel writer had a completely developed theology…they were too close to the events and still working them out. But through evaluation by the interpretive community and (I believe) with divine guidance, the original audiences compared notes and came to an interpretation that more closely resembled the truth. This is why I’m not all that worried about (early) scribal intervention. Making a “playlist” of your favorite writings as a form of authorship was pretty common in the early days of book making. It’s clear to me that John is a collaborative book. The usual view today is that it was compiled by the “Johanian community” based on John’s teachings (as you say, the ending speaks in the third person of the one who wrote these things). Likewise, Mark has always been seen as a collaboration between, at least, Mark and Peter. Luke admits from the start that his book is a compilation of eye-witness accounts.

I think your worry is that the original intent (a very hard to decipher idea) was seriously obscured by later scribal emendation. I really don’t think this is likely given just how many copies we have and how willing most scribes were to leave the weird stuff in. A good editor would have cut out the prophesies about the end of days coming 40 years after Jesus’s death if they wanted to clean things up…or at least fixed the inconsistencies about who got to the tomb first (and made sure it wasn’t a bunch of women). But these, in most manuscripts, are allowed to stand.

One other thing…

What if we actually had a manuscript definitively dated from 40 AD or so (I know…it couldn’t be any book from the New Testament which was mostly written later), which claimed that Jesus rose from the dead and repeated most of the stories in the Gospels (even in John). Sure, this would mess with our ideas of textual transmission and maybe cause scholars to revise our notions of when certainly theologies became widespread, but it still wouldn’t really be incontrovertible evidence that the documents told the truth. Joseph Smith wrote his account of the encounter with the angel Moroni(sp?) within years of when he claims the event took place, but you and I still don’t believe him (I assume). I love talking about textual criticism, but it doesn’t really seem to be very strong evidence for or against the historicity of the events the text records.

I have to admit that I did not have the stamina to read through all the comments. I have been catching up on my RSS feeds; maybe I will return to it at a later point. I just wanted to point out that many scholars believe that the original ending to Mark as we have it was not the intended ending of Mark - that is, that the true original ending was (somehow) lost and the later endings were tacked on by the church as an attempt to recomplete the story.

I am no scholar myself but I am somewhat sympathetic to this view. As it stands, 16:8 ends with ‘gar’, a conjunction; you just don’t end a story, especially long narrative-historic stories with a conjunction - even the choppiness of Mark’s Greek is not enough to overlook this glaring oddity. Also, the trajectory of Mark is clearly toward another meeting with Jesus in Galilee (14:28, 16:7), which Mark never gets to.

On the other stuff, I’d comment if I weren’t so tired, but 1 John 5:7-8 is my favorite example of church meddling in the affairs of Scriptural text.

Sorry to jump in so late, but I am just rereading some of your posts, just because I am interested, and the comment you made to Peter about not really writing to him, but to the fundamentalist caught me off guard. Aren’t us “liberal” Christians worse…I mean we know the evidence on both sides and we still believe in God. I would have though that you would have more sympathy for those that have been completely indoctrinated…considering you know what it is like. I didn’t grow up a Christian (fundamental or liberal), so I do not know where you are coming from on that account. I think you would have more of an impact on the fundamentalist if you did soften your approach, though. :) I don’t think I would be anything but raving mad after reading your blog if I was a fundamentalist. But that is just me, and I am not (although I think I was for a few short years). Anyway. I am glad that you think I am causing less harm…I hope you are right. :)

More than being a fundamentalist or a liberal, I really hope to be loving…I don’t live up to it most of the time, but I hope and wish that the word loving or understanding could more often be attached to Christians. “Right” or “Arrogant” seems to be more the ticket. And although we both hold a very high view of truth…truth without love doesn’t seem to get me anywhere…my daughters help to point that out to me daily.

Recent comments